Rotoscoping is, by definition, a technique where a live or animated subject is essentially traced over one frame at a time to create a cut-out of that subject, or a “matte”, which may be combined with another background. That act of adding a new background with foreground elements is called “compositing”. Rotoscoping Tutorials below shows you how:

The Rotoscope/ Rotoscoping Tutorials

The term “rotoscoping” is derived from a machine that performed an action similar to the one we describe in the first paragraph. A rotoscope was a piece of equipment that could project a single frame of the live-action film, which combined with an easel and a piece of frosted glass to allow an animator to trace the subject by placing a paper on top of the glass. By tracing each of the frames in a piece of film, the animator would end up with a perfectly accurate animation of only the subject they want to bring to life.

The rotoscope was created in 1914 by Max Fleischer, and first used in a three-part series called “Out of the Inkwell”. Fleischer created the series to show off his new invention. Max wisely patented his invention in 1917, and the amazing machine was soon being used to create big Hollywood animated pictures such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and Betty Boop.

A Beginner’s Guide to Rotoscoping in After Effects – No Film .

https://nofilmschool.com › beginners-guide-rotoscoping

In this post, we‘ve gathered the resources you‘ll need to get started with three of the most popular rotoscoping methods in Adobe After …

Rotoscoping: Everything You Need to Know – NFI

https://www.nfi.edu › rotoscoping

Rotoscoping (also known as ‘roto‘) is an animation technique that involves tracing over live-action footage frame by frame.

Understanding Rotoscoping for VFX Artists | Pluralsight

https://www.pluralsight.com › blog › film-games › und…

This article will give you an understanding of rotoscoping and its use, as well as some helpful tips when rotoscoping for your next piece of …

Rotoscoping has lived a healthy life since Max’s original invention and has been used prevalently in productions for television and feature films. One dramatic example of a rotoscoped piece is the A-Ha music video, “Take on Me”. The groundbreaking video features shots that look like photorealistic drawings, animated using an interesting technique called “boil” or “jitter”. The effect is evident through the shaky nature of the lines of the animated subjects. This effect is usually unintentional, and the result of careless or inconsistent tracing, but in A-Ha’s case, the effect is intentional and gives the video its iconic look.

How Long Does It Take? / Rotoscoping Tutorials

Now, considering the process discussed above where each frame of film is traced to create an animation, how long would a four-minute music video take? “Take on Me” took over 16 weeks to trace over 3,000 frames of live-action video.

These days, the bulk of rotoscoping takes place on computers using programs such as Imagineer’s Mocha Pro, Adobe After Effects, and Silhouette. Each of these programs has been optimized with tools to simplify the roto process.

The most popular – and timely – example of rotoscoping work in Hollywood would be the lightsabers in the Star Wars movies.

To create the effect, the actors would act out their choreographed saber battles using sticks. The rotoscope artist would then rotoscope the stick frame by frame, adding a glow effect. The effect was further sold by extensive audio effect work.

Why Do People Dread Rotoscoping?

Rotoscoping is one subject people that are into production or post-production dread a lot. This is because moving pictures use a lot of frames. Shoot ten seconds of video at 24 frames per second and you’ve got a 240 frame roto project on your hands.

While in many cases, the process has to take place, but often a designer can avoid rotoscoping by working with shots that have been carefully shot on a green screen. Powerful software can identify the color of the screen and remove it, creating a matte for the duration of the shot, saving having to create the matte one frame at a time.

When Is Rotoscoping Necessary?

Even in the best projects with the ultimate professionals, things can happen. One potential issue is when an actor’s arm, leg, or other body part moves outside the area of a green or blue screen. To create a clean matte, the only option would be to rotoscope out the errant extremity and use software to do the rest of the work. In most cases, there should only be a couple of seconds with the issue, but if a director is careless this could be a huge issue.

In another case, if the director is flawless but the set team didn’t properly set up a greenscreen or light the thing properly, roto can play a part in the post-production. Fabric-based backgrounds can wrinkle, creating shadows that the software won’t remove, and poor lighting can do the same. In this case, even a shot that should have been a breeze to work with can create a roto nightmare.

Of course, there are differences between using software to remove a green screen and manually rotoscoping out a subject.

When software clips out a matte it will remove pixels that match criteria set up by the designer to “key” out a green or blue screen and nothing else. Manually rotoscoping leads to hard edges, as we will be clipping a very specific line. Effects can be added later to soften the lines and blend the subject into a background, but it’s important to note the difference.

Rotoscoping – Best Practices

To start, instead of simply choosing a random frame in the clip and tracing the head and body of the subject with the pen tool (this is called creating a “mask”), give the project some thought before selecting anything. Depending on the motion or movement of the subject, the tracing points could vary pretty drastically throughout the length of the clip.

It would work to simply select the outline of the entire subject, but if the motion is, say, walking, body parts will pass in front and behind one another, and many body parts will bend, dip and sway.

Instead, consider carefully how the body will be moving, and try looking at the body as a handful of basic shapes. Now instead of creating one large mask, use multiple masks for body parts, including separate masks for joints. As the subject moves from frame to frame, you’ll have a great construct of masks to simply reposition and tweak.

Many artists will actually place their masks on their own layer, separate from the footage so that they may be turned on and off without affecting the video layer. Depending on the software you choose this might be an option.

Receiving clear instructions of which portions of footage are going to be used can save tons of roto work. If you’ve got 25 seconds of footage at 30 frames per second, but the project only requires four seconds of the clip, ask which exact four seconds need to be roto’d. Rotoing 120 or so frames is much better than 750 of them.

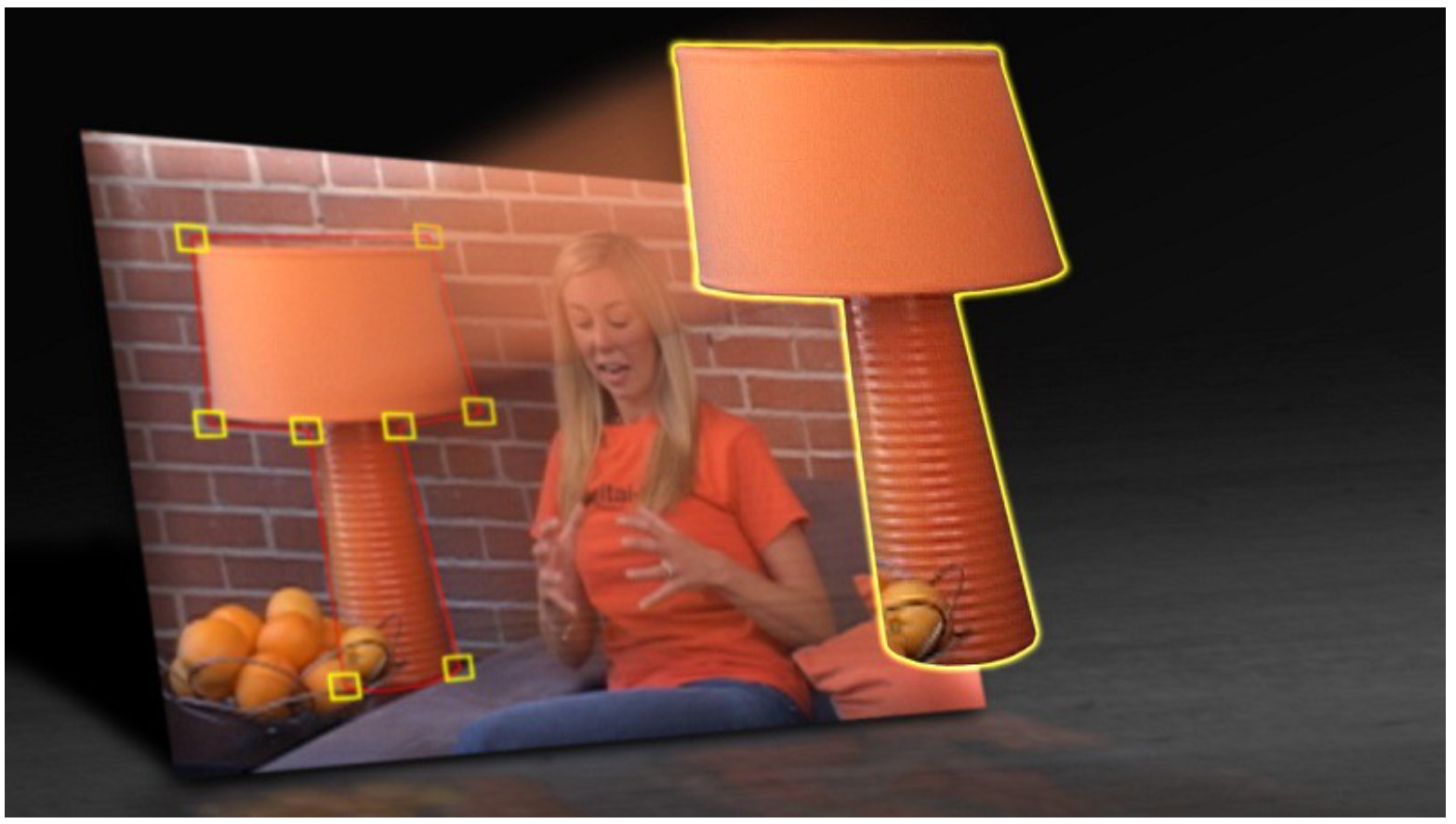

Rotoscoping Simplified

A few years ago, the brilliant After Effects team at Adobe created a tool called “Rotobrush” in an effort to simplify rotoscoping. The idea is that the After Effects designer has a tool to use similar to the “Quick Select” tool in Photoshop to trace over a subject. The tool can select anything that stands out somewhat from a background. And can be tweaked to find subjects more accurately. Once the tool has a hold of the subject, it can track forward and backward through the footage. And the tool will adjust to keep the subject selected throughout the entire clip. It doesn’t always work perfectly, but, like any rotoscoping job, there are best practices.

Still, if you can make it work for your project it can save you many hours.